Financial Crises: My Debts, Part Four

In the early 2000s, the rug got pulled out from under education just as Wall Street nearly destroyed the entire global economy. How did I get through graduate school? By taking out more loans!

In 2003, while still living in Japan, I started getting ready to move back to the States.

I simply had to go to grad school, I realized. If you knew me back then you’d be in awe of how much of a nerd I had become. I mean, just listen to this: shortly after I moved to Japan, some friends introduced me to a bookstore that sold English-language books. I spent hours there, scouring the store’s shelves for serious sociology books published by university presses. (I found a copy of Importing Diversity, a really good study about the very same exchange teaching program that brought me to Japan.) Later, I signed up for this new website called Amazon that would deliver books to me, and yes, I found myself doing serious reading on Muslims in the West (I also read the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy while I was in Japan, but somehow this seems complimentary to my point that during this time, I established myself as an out-of-control nerd for social science.)

I knew I wanted to become a college professor, doing research and teaching sociology. That meant I needed to get a Ph.D. Sounds good so far—but what about the tens of thousands of dollars in student loans that I still owed? Could I really afford to go to graduate school? Unlike when I went to college back in the 90s, here in 2003, I knew more about the perils of student debt, and I wanted to avoid having to take on more loans. Even better—I wanted to keep paying down my existing debt, rather than allowing interest to pile up while I went back to school.

To Defer or Not to Defer

The decision to go to graduate school was, unquestionably, risky. Even I knew that, in 2003. Grad school in sociology would take me at least six years—I’d be in my thirties by the time I graduated. Unless I got a “full ride,” I’d have to pay for tuition, fees, books, etc. while in grad school. Not only would I need to give up on the opportunities (fledgling, but real) I had to build a career in Michigan and/or Japan, I’d also have to live with limited income for at least six years. If I wanted to earn money, going to graduate school for sociology was probably not the best idea.

It was only the tremendous potential the lifesyle offered by a tenured job as a professor—dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge and teaching—that kept me going on this path. That, and a lot of naïveté. Although I learned a lot about “the real world” by teaching English in Japan for two years (that’s a story for another day, though), at 24 years old in 2003, I didn’t fully appreciate just how huge of a risk I was taking.

I understood that graduate school was going to be a bad idea for my short-term finances, but I decided that finances weren’t that important to me. This was a privileged perspective, which came from having a supportive family and the fact that I “graduated well” from college (with a lot of debt). (Please listen to Tressie McMillan Cottom and Louise Seamster on the “graduating well” concept and student debt in general—seriously, go listen right now.)

What’s more, I thought, if I found a graduate school that offered me a good financial aid package, I could afford to keep paying down my existing student debt. That would mean I didn’t have to “defer,” or stop making payments while in school. Deferring, I clearly understood, would mean the amount I owed to the banks in the form of interest would keep growing.

Would I find a graduate school willing to pay me to study sociology?

California Dreaming

Long story short, I decided to go for it. Graduate school, here we come!

I enrolled at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and prepared to start classes in the Fall 2003 quarter (UCSB uses the quarter system, instead of the more common semester system—this will be important in a moment).

Part of why I decided to go to UCSB was the generous financial package that they offered me. Because I had no conception of what graduate school finances would look like, I didn’t ask many questions, though. Only after arriving in California did I realize that I had been misled by the university.

The UCSB program presented me with a very generous financial assistance package that would pay my out-of-state tuition for my first year (during which time I would establish residency in California), and in addition I was given a scholarship with a stipend of (as I recall) $25,000 (or $36,000 adjusted to 2022 dollars). Furthermore, I was guaranteed a job at the university, working as a Teaching Assistant. This meant that I would have my in-state fees paid in full, making my education entirely no-cost to me. And, I would earn wages of about $10,000 per academic quarter for three quarters (Fall, Winter, and Spring—with no summer income). In total, between wages and the fellowship’s stipend, I’d earn about $55,000 (adjusted for inflation: $80,000 in 2022)! Not bad for a graduate student, even in the quintessentially high-cost-of-living area that is Santa Barbara.

Making $80,000 per year (in today’s dollars) as a graduate student, I thought, I definitely won’t need to defer payments on my student debt from undergrad! I’d have enough income to easily afford to live as a single guy in Santa Barbara, and I figured I wouldn’t even need to take out another student loan.

As I arrived in Santa Barbara in the summer of 2003, where the weather was (of course) perfect, I thought I was on a glide path to success. What could possibly go wrong?

Financial Crises

Yeah, so other than the weather (which was always perfect), things at UCSB started to look a lot less sunny by 2004.

As it turned out, the financial package that UCSB offered me for 2003 would only last for one year. The UCSB folks who recruited me did not explain this to me. (This should sound familiar, if you’ve read my other story about the time I was taken in by misleading financial aid packages.)

Instead of clearly explaining that after the first year, my financial aid package would be much different, in 2003 UCSB led me on, saying (as I recall) very little about financial support for my graduate education in years two through six (and beyond). And, because I was the first member of my extended family to go to an academic program in graduate school, I didn’t know how to ask questions about the financial package such as: “What financial support will the university offer me for my whole time in school?” I assumed—mistakenly—that I’d have the same generous financial support package for the duration of my graduate education.

If I had asked better questions, I would have learned that after the first year, the university would offer me absolutely zero dollars of guaranteed support. Starting in 2004, I’d have to find jobs, apply for grants, try to win fellowships, and—yes—take out student loans to get financial support for graduate school.

So, by the spring of 2004, I belatedly came to the realization that my cushy $80,000 annual income (in 2022 dollars) would very quickly dry up. This was my first graduate school financial crisis. I worried that I’d made a terrible mistake, and for a time I did seriously consider whether I should change my plans.

Meanwhile, the talk of the town around UCSB was all about the university’s unprecdented “budget crisis.” Yes—just as I arrived at UCSB in 2003, California enacted “deep cuts” to its support for higher education ($250 million less, or a cut of about 10% compared to the prior year). For me, this meant that there would be fewer jobs to go around for TA’s. I’d have to compete with my fellow graduate students for a limited number of jobs.

For those keeping score at home, that’s two financial crises in 2003, one personal and one institutional: both right as I started graduate school.

Graduating Well

The good news is that my relatively plush income for that first year allowed me to prepare for the new era of austerity at UCSB. Also, my decision to (try to) learn Arabic as part of my graduate education provided me with an unexpected opportunity. I applied for and received two fellowships to study Arabic, in 2004 and 2005.

What’s more, thanks to the expert advice of my peers and colleagues, I used the struggle for graduate school funding as a chance to learn about grant writing. I applied for several grants, and while I got turned down more often than not, fortunately I did manage to get these grants funded a few times. I am particularly proud of my grant from the National Science Foundation, and I was among the very first students to win generous grants from the Richard Flacks Democracy Fund. My dissertation advisor also arranged some extraordinary funding for me that enabled me to travel during the most crucial phase of my dissertation research. I am grateful and still surprised that these institutions provided me with this support.

However, even with all of this tremendous support, I could not get through eight years at UCSB without taking on additional student debt. First of all, I ended up deferring payments on my original loans from Albion College. This meant that my debt burden increased significantly, due to interest on the over $20,000 in loans that I already had taken on.

And yes, in order to pay the bills (housing in Santa Barbara, infamously, does not come cheaply), and to avoid taking on additional off-campus jobs, I took out student loans for three of the eight years that I was in graduate school.

These additional loans may have technically paid my utility bills and rent, but in reality, they paid me in time. Because I took on that financial debt, I did not have to spend hours working at a job off campus. I was able to use that time, instead, to meet with my professors, to read an awful lot of sociology, and to write and re-write my dissertation.

By January 2008, I was on my way to graduating well. I set a plan to graduate by 2009, “on time” at six years after I started. I began eyeing a trip to the academic job market, to find that tenure-track job as a professor of sociology. Finally, the goal I had set back in 2001 was within reach.

Financial Meltdown

Then, suddenly, as I was writing my dissertation in late 2008, Senator John McCain took the unprecedented step of “suspending” his campaign for president against Senator Barack Obama. The economy, McCain said, “was about to crater.” McCain’s prediction proved correct, of course. By the end of 2008, several major Wall Street Banks had collapsed, and the Great Recession continued on until 2009.

The timing of this economic meltdown could not have been much worse for anyone, like me, who was looking for a job. Especially if tens of thousands of dollars in student loans would come due as soon as you left school, the prospect of the recession drying up all job opportunities seemed extremely daunting. (I didn’t want to default!)

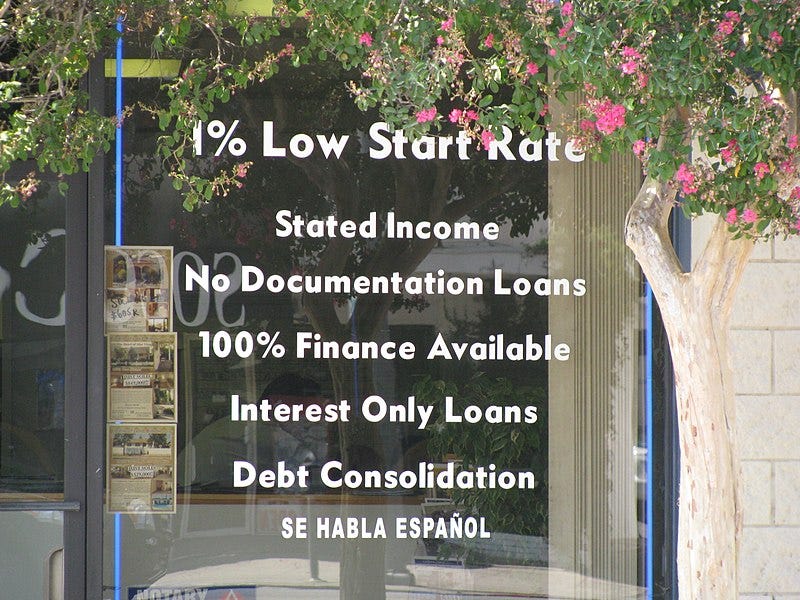

Now, with the global economy literally entering free-fall, the dual financial crises I experienced in 2003 seemed quaint by comparison. My troubles were, in fact, fairly tame compared to my peers. Many of my fellow graduate students who went on the job market in 2008 and 2009 found that job offers and searches were being cancelled as colleges and universities went into hiring freezes amid the global economic crash. Their lives were thrown into turmoil, as of course, were the lives of the millions of people who lost their jobs and who had their homes foreclosed upon by the very same banks that caused this mess.

Luckily for me, I was able to extend my time as a student at UCSB, deferring payments on my loans, until 2011. This gave me time to work as an adjunct instructor of sociology at a very nice place called Dickinson College, which I did while revising my dissertation. (Thanks to my colleagues at Dickinson for taking a chance on me, even before I finished my degree. More on this in Part Five!)

Help on the Horizon?

So, gainfully employed with my Ph.D. in hand in 2011, some ten years after I had finished my time at Albion College, I began making monthly payments on my student debt.

As I kept paying my student debt bill, again and again, every month, I read frequently about a new program that had started in 2007. Congress enacted the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program (PSLF), which was designed to allow people working in “public service” to have their student debt forgiven after making ten years’ worth of payments. I checked, and rechecked, to confirm yes, college professors at non-profit institutions (like where I had worked since 2009) would qualify as “public service” workers.

Well, I started my loan payments again in 2011. Instead of paying for the next fifteen or twenty years, perhaps I could have all of my loans forgiven ten years later… so, 2021?

If you were me in 2011, would you not not hold out hope for this? The Obama years seemed awfully hopeful. Even after President Obama presided over the Wall Street bailouts, leaving regular folks mostly on their own to avoid foreclosure, still—this seemed different. Student debt had the potential to tank the economy, in much the same way as “subprime mortgages” did in 2008. Surely, this time, the financial system would make the corrections it needed to avoid systemic shocks.

In 2011, as I logged in to Navient and Great Lakes student loan servicing, every month, I remained hopeful that each payment was getting me closer to Public Service Loan Forgiveness. “By 2021,” I thought to myself, “all of these debts will be wiped away….”

Next Time

Well, 2021 has come and gone. Was 2011-Erik right? Were my loans forgiven? Sorry, but you’ll have to tune in next time to The Love Letter to find out.

By the way, I’m now finished sketching out the rest of this series on My Debts. This was part four, and I think I’ll be done after part six. We’re almost there. Thanks for sticking with me. Let me know what you think in the comments, and reach out any time with ideas, questions, criticism, feedback, commiseration, song recommendations, and anything else you’ve got for me. I really appreciate you being here.